Veronika's Garden of Un-celestial Torments

According to Martin Heidegger, “death is the most original form of the possibility of Existence that threatens the entire universe. Unlike any other living creature, humans are terminally affected by destruction and death.”

Death, an unyielding theme, serves as the linchpin of human evolution, history, philosophy, religion, and art. Deeply rooted, it is both feared and venerated. For millennia, death has woven its narrative through human myths, sagas, and tales, emerging as the ultimate threat and the ultimate punishment. It is no surprise that the urge to escape mortality or inflict death has etched itself into the human psyche. We are acquainted with stories of reincarnation and resurrection, as well as the dark pleasure some find in inflicting torment leading to death.

The concept of death remains incomprehensible and unacceptable, giving rise to dreams of immortality and the afterlife, birthing the notion of Purgatory. As Waldemar Januszczak notes, “Purgatory is somewhere between Earth and Heaven. That’s where you go if you have not been bad enough to go to hell but had not been good enough to go to heaven either.” Purgatory is an interim in-between state, a form of existential superposition.

And the haunting ambiguity persists—the “in-between” that holds both punishment and suffering. Why is the nether-neither-world between life and non-death fraught with torment? Furthermore, why does the Earth world, even today, remain a canvas of destruction, mayhem, and cruelty? Can history offer us any lessons? What fuels our persistence? Is it the thirst for life, the drive to survive, or perhaps curiosity? What fuels our growth? Instructive, wise narratives? Art? And what impedes our journey to creating heaven on Earth? Why do we cling to the notions of hell and purgatory?

Is it ignorance, perhaps?

Ignorance lacks the power to discern between truth and falsehood. It breeds the feeling of uselessness, redundancy, helplessness, and anxiety. The power-less are easily seduced by power, and the lethal mix of anxiety and power erupts into anger, shrouding everything in disorienting darkness.

Hannah Arendt cautioned us. “Neglected and forgotten people yearn for a narrative, even a fictional one, that would eliminate their anxiety and promise redemption. Authoritarian power exploits these anxieties, creating a fiction that people willingly embrace.” A fictional story that promises to solve one’s problems (helplessness) is much more appealing than facts and “reasonable” arguments. Arendt warned against succumbing to nihilism, cynicism, or indifference, advocating instead for transcendence and illumination.

Returning to the question of what sustains and propels us, what gives us hope—In his article “How to Save a Sad, Lonely, Angry and Mean Society,” David Brooks asks: “Does consuming art, music, literature, and the rest of what we call culture make you a better person?” David Brooks argues that we “don’t bother practising to enter sympathetically into the minds of their fellow human beings. In his view, we are “over-politicized and increasingly under-moralized, under-spiritualized, and under-cultured.” The alternative, he suggests, is to “rediscover the humanist code.”

Artistic creation is a fundamental human act. Most of human activity, throughout history, has been forgotten, surpassed, or had to be revised, adjusted, and updated or contemplated disdainfully or at least with a grain of salt. There is only one exception. Despite the passage of millennia, art stands its ground, commanding awe and respect. It teaches us how to live; how to exist.

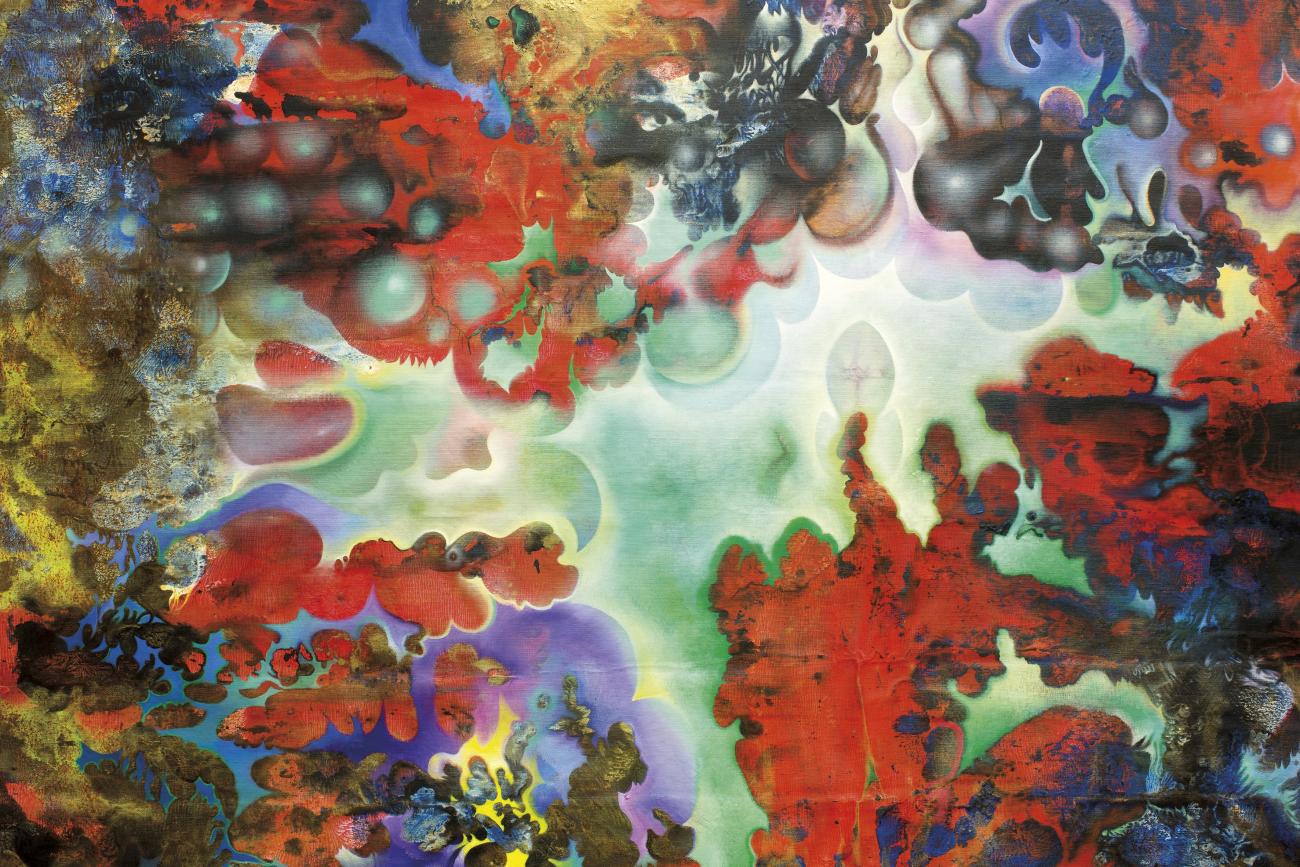

Veronika's artistic signature, her virulent, explosive blend of an inexhaustible source of ambiguity, serves as a stargate into the neither-world, where darkness and lucidity rule, side by side. Her garden of celestial delights can, in a millisecond, morph into a garden of un-celestial torments. Ambiguity possesses the power to dismantle our primeval cognitive defenses and elevate our empathy skills. Veronika cares—about everything and everyone. She collects memories of all existence and humanity. Her meditative worlds, or better yet, nether-neither-interim-worldscapes, undulate in a binary algorithm, simultaneously attractive and repudiating, abhorrent and charming, cuddly and outrageous. Her cultural memory encompasses and transcends billions of years of evolution, providing the much-needed transcendence and illumination.

Lumír Hladík, Toronto

January 2024